Published on:

13 October 2023

Share this:

Question: What happens when nine young people from around the world gather in Sri Lanka to discuss how to protect vulnerable communities from destructive floods?

Answer: A “Flood Green Guide Youth Champions Program” is born, with the goal of inspiring the next generation of leaders to become change agents in their communities and advocates for nature-based approaches to flood management.

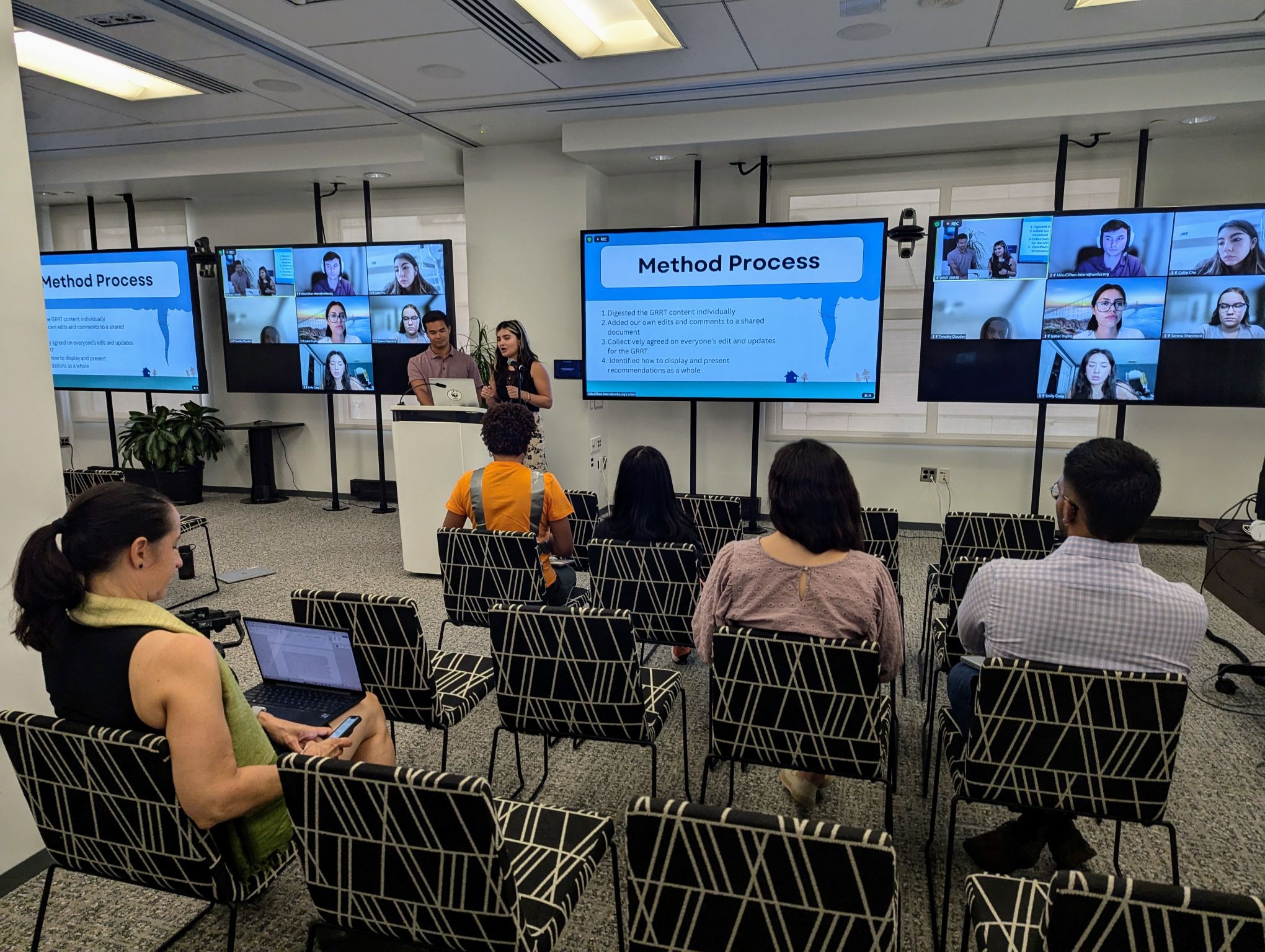

These nine young leaders from Africa, Asia-Pacific, and Latin America and the Caribbean were chosen from over 400 applicants ranging in age from 24-30 for a pilot program developed by World Wildlife Fund (WWF). During a week full of strategy and training sessions, role playing games, and instruction from leaders in flood management, they gained a foundational understanding of nature-based flood risk management, disaster risk and climate change adaptation concepts. But the main output of the pilot program was to co-create a youth engagement program that meaningfully incorporates the knowledge and ideas of youth at the forefront of the climate crisis.

The workshop was supported by the Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Centre and Youth for Resilience initiative, and held at the Sri Lanka Institute of Development Administration.

The youth champion initiative North Star is Natural and Nature-Based Flood Management: A Green Guide (Flood Green Guide), developed by WWF in partnership with the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID/OFDA). This step-by step guidebook for flood managers provides practical tools and guidance to understand the basics of flood risk management planning. The Flood Green Guide has served as an essential resource to municipal governments, community groups and nongovernmental organizations and is supported by an in-person and online training program.

“It’s opening our eyes on how we can harness the power of young people in securing our future,” says Jeannette Iranzi, Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning Officer for the youth-led NGO Nature Rwanda. “I’ve been displaced by flooding in my community with other people, and so by contributing to this kind of program, I feel like I’m coming from vulnerability to resilience.

Globally, flooding is the most common disaster risk affecting all segments of society, including youth. As cities grow and climate change increases the severity of extreme weather events, flood risk is on the rise. Children and youth, however, are often not included in disaster management efforts and decision-making, even though they represent more than half of the world’s population.

“Today’s young people are tomorrow’s flood managers and disaster risk reduction experts, and they’re critical now to advancing effective and just flood risk management efforts,” says Anita van Breda, Senior Director of Environment and Disaster Management at World Wildlife Fund. “Who better to engage and support to solve these problems than a young person in Uganda or the Philippines who has seen the damage that floods and other hazards can have on their communities?”

Sri Lanka has not been immune to severe flooding, which is one of the reasons it was chosen as a location for the workshop. The small island nation southeast of India suffers from serious flooding, including devastating floods in 2016 and 2017 that killed over 300 people and displaced hundreds of thousands. The country is home to the International Water Management Institute, a research agency focused on improving how water is managed to help improve food security, reduce poverty, and protect the environment.

The workshop included a site visit to explore Colombo’s urban wetlands, including Diyasura Park, to inspect nature-based flood management in action while learning from the wetland park managers. The wetland system and park are important to the country’s flood management while supporting local biodiversity and ecology, including migratory birds and fishing cats. In addition to flood management, the park also provides the local community with livelihood opportunities based on ecotourism.

After learning about the Flood Green Guide, workshop participants shared their own experiences in youth engagement – what has worked and what hasn’t. They learned from each other’s experiences and compared them with their own countries. Shreya K.C., a climate justice activist who has been featured in two books, including “50 Girls Who Are Saving Our Planet,” described growing up in Nepal and experiencing firsthand the impacts of flood and landslides.

“It had a profound impact on me, and I’ve been compelled to understand its cause since I was a child,” Shreya wrote in a blog following the workshop. She also highlights the importance of intergenerational and intercultural collaboration by quoting The African proverb, “Youths can walk fast but elders know the way.” This “rings true in the case of flood risk management,” she adds. “Youth can be harnessed as bridges between generations and segments of society.”

Environmental engineer and a member of Paraguay’s Youth Network for Climate Action Agustina Benitez focused on technology as one of the best opportunities for young people in flood management. “Our up-to-date knowledge in technology allows us to explore new ways to face the challenge,” she wrote. Benitez was impressed by a presentation from Nilakna Warushavitana, a young Sri Lankan who developed a mobile app that uses augmented reality to help people explore wetlands in Sri Lanka and learn about their importance for flood management.

By the end of the workshop, exhausted but enthusiastic, the group designed their team roadmap for the next six months and developed activities for long-term engagement, with the goal of finalizing the design of the Youth Engagement Program forthe Flood Green Guide. They identified the major problem with flood management as a lack of capacity building and financing for engaging youth. This hinders decision making and innovation, they concluded. They drafted three objectives for the program: 1) building capacity for community and youth empowerment in flood risk management; 2) establish youth-focused spaces for civic engagement and decision making in flood risk management; and 3) increase targeted funding to support youth innovation in flood risk management.

“It was important that this program was designed ‘by youth for youth,’” notes Luz Cervantes, WWF Senior Program Officer, Environment and Disaster Management. “WWF and its partners can provide the building blocks, but to identify the existing barriers and opportunities for engagement we really need to involve young leaders, who are so well connected to the mindsets of youth in their countries.”

Some of the solutions they identified include online and in-person training programs and soft skills development in nature-based flood management. To build the capacity of youth, they recommend the development of a Flood Green Guide Youth Network and a space for dialogue between youth leaders and decision makers. And to support youth with finance and technical skills they recommend developing an exhibition of innovative solutions and projects, international funding dialogues, and a workshop for proposal writing and project management.

Finally, they all concluded that making important connections through the workshop will greatly benefit them as they build youth movements in their own countries.

“I’m going really happy to my home because now I have new friends from all over the world,” says Colombia’s David Urueña, a geologist and disaster risk management consultant. “I have an expanded network I can talk with about these kinds of issues that we have in our countries, and we can share possible solutions. We are doing something really great creating this program.”