Published on:

10 May 2022

Share this:

WWF Guatemala held a Flood Green Guide training in August 2021, which targeted local government employees from various municipalities. In this piece, Edgar Ramirez and Carlos Telon, who both attended the training, tell us about their flood-related work taking place in two different watersheds, and explain how they are incorporating nature-based solutions into flood management.

Edgar Ramirez, Municipality of San Lucas Sacatepéquez

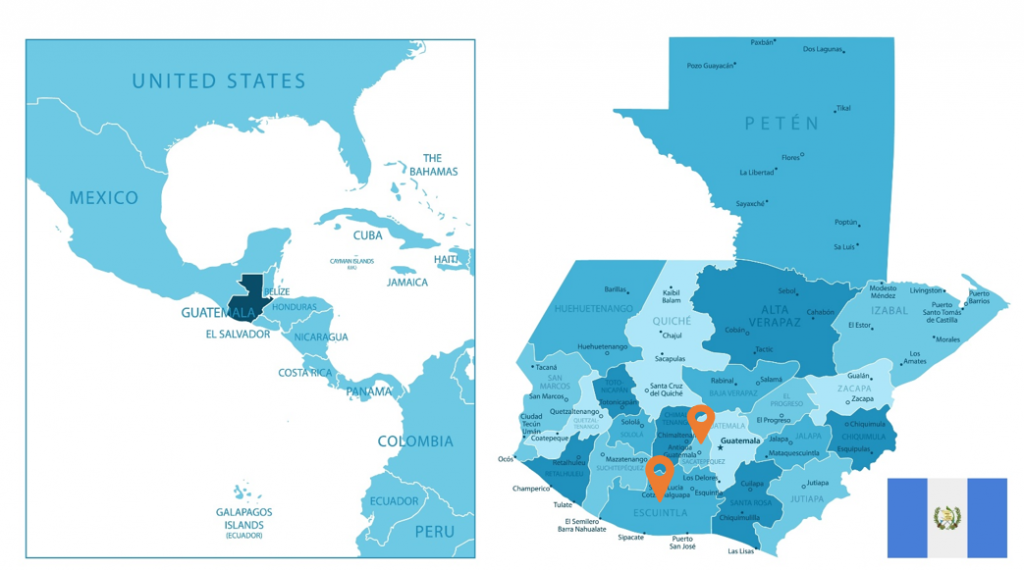

Edgar works as a Risk Management Specialist at the Municipality of San Lucas Sacatepéquez, located 27 km from Guatemala’s capital. His municipality has about 30,000 inhabitants and belongs to the upper watershed of Lake Amatitlan (Fig. 2), in the Michatoya watershed. They are located ~4265 feet above sea level and their municipality is abundant with forest and freshwater ecosystems. Southwest of San Lucas Sacatepéquez is Antigua Guatemala, which is well known internationally.

Which types of floods do you have in your municipality? Are natural and nature-based methods used to manage them?

We don’t have many floods in our municipality anymore. Historically, floods only occurred in the winter season, and work to address those started years ago. Due to our geographical location, the water travels down from here toward other municipalities, and in some cases leads to floods. So, with that in mind, even though we do not have many floods in our municipality, we are working on multiple reforestation projects to preserve these ecosystems and avoid runoff to other municipalities. The administration of former San Lucas Sacatepequez mayor Lic Yener Haroldo Plaza Natareno also built more than 300 wells that are located on roads identified as most critical in terms of water flow. These wells help recharge the water table as well as reduce the risk of flooding in the municipalities of the lower watershed.

How often are nature-based methods used for flood management in your region? What is the reason for this level of frequency?

Generally, the use of nature-based methods is not very common. We were very privileged to take the Flood Green Guide course because I think it opened our eyes to the wealth of options for managing flood risk. I really appreciated when we talked about creating partnerships and involving other institutions (such as companies and NGOs) in this work. Sometimes people believe that the key to implementing these projects is funding, but that is not necessarily true. To me, it is key to ensure that government authorities know the importance of preventing floods. Another barrier that we have seen regarding the use of nature-based solutions is the lack of political will of the institutions in charge.

Which tools and concepts did you learn in the training that will be useful for your work? How are you planning to apply those tools?

First of all, the workshop opened our eyes to what a flood really is. I thought that the impact of floods was only immediate, but now I understand that they can impact the economy, health, education, and human well-being. In terms of applying the work in my community, we are currently in a growth phase at the municipality and I hope that next year we will have the budget to hire additional people to do more field work and to be able to apply the knowledge of the Flood Green Guide.

I encourage you to continue promoting the methods of the Flood Green Guide. Often no action is taken due to lack of knowledge, but once one knows about the subject, they begin to become involved. And I really believe that the best way to act is to prevent floods, not just right before the rainy reason, but long before. We must work to implement non-structural methods including through legislation, education, and securing funding to invest in new projects.

Over the past couple of years, devastating floods have claimed lives and overwhelmed communities around the world. As the climate crisis worsens, what do you see as the most urgent needs in countries that are particularly vulnerable to flooding?

Environmental education. I believe that more awareness is needed in terms of the management of waste, forests and land because often environmental issues like deforestation cause many problems. In Guatemala, many problems are also due to waste. When it rains, debris travels and forms barriers, causing additional problems.

At the municipality, we have worked with schools to teach young people and children environmental education, including about climate change. Most adults are reticent to act and say nothing is wrong; young people are the ones making the change.

Figure 2. Lake Amatitlan.

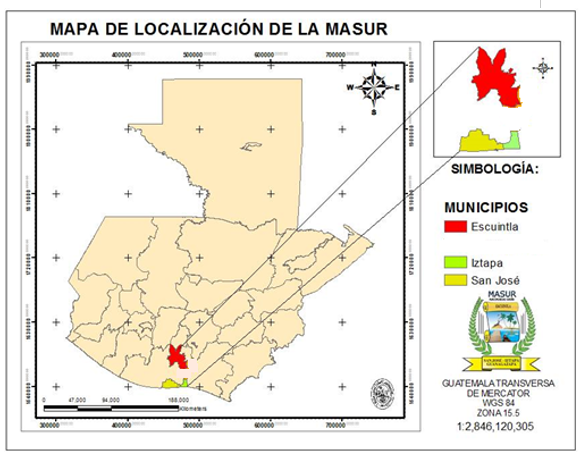

Carlos Telón, Mancomunidad Surena, Municipality of Iztapa

Carlos works at the Mancomunidad (an association of municipalities) “Sureña – MASUR”, which includes the Iztapa municipality, where he lives. His municipality has about 19,000 inhabitants and is part of the Maria Linda River watershed. They are located in the lower part of the watershed, where the river meets the sea (Fig. 3.).

Tell us a little bit about the municipality where you work.

Iztapa is one of the three municipalities in the Mancomunidad Sureña. We have an important ecological asset: about 1,600 hectares of mangroves. It is very important for us to maintain that natural resource, not only for the municipality, but also for the nation and the world. 40% of our territory is susceptible to flooding. Luckily, we have a climate action plan in the three cities that are part of the Mancomunidad, which details all the actions that we are going to carry out in terms of managing floods, solid waste, and more. Our climate action plan was born from our inventory of greenhouse gases. We report to CDP’s cities program and the Global Covenant of Mayors, so we are very involved in these issues.

What methods are used for flood management in your municipality? How often are natural and nature-based methods used?

60% of Iztapa is occupied by sugarcane fields. Within the farms, a series of canals were established parallel to the river to serve as irrigation, and also to mitigate floods during the winter. Now, floods are no longer as severe as before because the water comes down with less pressure. In my community, we used to always get flooded, but not so much anymore since these canals were built, unless it’s a really bad flood like during Hurricane Mitch.

In addition, with WWF Guatemala we have a reforestation plan, which was born from the municipality’s climate action plan. We are working to maintain the forest nurseries in the area and this year we are going to initiate reforestation efforts. We have also done many workshops to make people aware of the importance of mangroves.

In parallel, we are also working in the area of solid waste management, which impacts the issue of flooding. Our municipality receives a lot of waste since we are in the lower part of the watershed, and we are also part of the sub-watershed of the Michatoya River, which is the outlet of Lake Amatitlán, where all the waste from Guatemala City ends up. Right now, we got access to a project supported by the European Investment Bank that will help us categorize the waste of the 3 municipalities and develop a methodology for solid waste treatment in line with European standards.

What do you see as the most urgent needs in countries that are particularly vulnerable to flooding?

We have to build resilience. I think it is important to have the infrastructure to shelter the population at risk. Fortunately, in our municipality we have very good infrastructure, such as schools and community halls that can house the population in the event of a very strong flood. Bridges have also been built that allow us to connect with isolated communities.

The issue of monitoring is also important. We have a good network since we work with the Climate Change Institute (ICC), which has stations to study the climate, the intensity of the rain, and more. So now we have better knowledge of the climate variability in this area.

Which tools and concepts did you learn in the training that will be useful for your work?

It was really interesting to see how important the knowledge of the watershed is. During the Flood Green Guide training, our group didn’t work on a hypothetical watershed. Rather, we worked on our own watershed, the Maria Linda watershed. Through one of the group exercises, we realized the extent of the area that we need to protect. We want to restore some of the biological corridors that border the river, and we identified some areas that haven’t been covered. The good news is that we are partnering with a network of professionals who work in restoration and together, little by little, we will do the work.